| This Newsletter is being published on a quarterly basis pursuant to CBD decision IX/7. To subscribe, please visit http://www.cbd.int/. The aim of this e-Newsletter is to facilitate sharing of information on the application of the ecosystem approach and promote the use and voluntary update of the Ecosystem Approach Sourcebook. | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ecosystem Approach and Invasive Alien Species

Besides, this issue introduces two recent publications produced by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), on the application of the ecosystem approach to marine spatial planning as well as biogeographic classification of global open oceans and deep seabed. It also introduces the report of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) on highlighting critical connections between water security and ecosystem services. This issue was prepared in partnership with GISP, UNESCO, UNEP, and the UK

Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC). | ||||||||||||||||||||

Global Invasive Species Programme (GISP) promotes the ecosystem approach as being essential to the effective management of biological invasions Invasive alien species are plants, animals or micro-organisms whose introduction and/or spread into a new ecosystem to

which they are not native threatens biodiversity as well as food security, human health, trade, transport and economic development.

Biodiversity is impacted negatively in a number of different ways including; competition, predation and herbivory, parasitism and

pathogenesis, hybridization, facilitation e.g. by changing nutrients, air or water, and ecosystem processes but in all cases,

the impact of the invasions and indeed the reason for the invasion phenomenon, is the interaction of the invasive species and

the recipient ecosystem.

For this reason, GISP actively promotes the ecosystem approach in the management of invasive species so that the target is not just the reduction or eradication of the invading species but involves the recipient ecosystem and includes community involvement in a multisectoral, multi-tiered approach. A good example can be found in the UNEP/GEF-funded project, ‘Removing barriers to invasive plant management in Africa’, currently being executed by CAB International (CABI) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which has adopted the ecosystem approach in managing invasive species at pilot sites in four countries in Africa. The project focuses on managing invasives at the lowest level appropriate with the involvement of all stakeholders but notably, the local community (principle 2). A great deal of emphasis has also been attached to the importance of ensuring inter-sectoral co-operation including the formation of inter-ministerial bodies, which is consistent with the 5th operational guidance point in CBD decision V/6. Another important aspect of the ecosystem approach is that it encourages consideration of why management of a biological invasion is necessary and why it should take place before developing a management process. This latter aspect is necessary in order that stakeholders can debate and decide the expected outcome of management options for such targets e.g. returning the affected ecosystem to its original state (if that is known), or to a state where the invading species is diminished in extent, vigour, spread and/or impact on either the whole ecosystem and the surrounding local community, or the revitalization of selected important species and populations within it. GISP has experienced many examples where the management of invasive species, which is based solely on eliminating the target species, has not yielded the desired result. Most common is the situation where the removal of an invader is achieved and then the degraded ecosystem becomes susceptible to further invasion by another invasive species e.g. removal of the aquatic invasive, water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) from a lake often results in an invasion by another invasive species such as the water fern, Salvinia molesta. This type of problem can be addressed by careful planning for an agreed and desired outcome of management – using the ecosystem approach. Ironically, there are also examples where the continued presence of an invasive species at a lower density can be of value to the ecosystem e.g. by providing new nesting sites, or to people reliant on ecosystem goods and services that have been enhanced by the invasion such as provision of novel food sources, fibre, fuel, materials for artifacts, etc. Use of the ecosystem approach in planning and implementing the management of invasive species on islands is a good example, in which many types of stakeholders can be consulted as well as components of the affected ecosystem analysed and outcomes debated. Nevertheless we still see some situations, especially where the total eradication of predators is concerned, where secondary and tertiary impacts of their removal have had deleterious effects on species of special importance. This is increasingly being addressed using the ecosystem approach to model possible outcomes of management and to better define the expected outcomes in terms of ecosystem indicators rather than the survival and population growth of selected species. As more work is done to understand biological invasions on larger landmasses, often with more complex matrices of habitats and species, it is clear that the ecosystem approach can assist to define and achieve desired outcomes.

|

||||||||||||||||||||

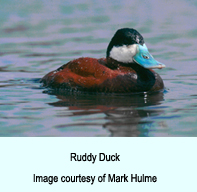

UK Ruddy Duck Eradication Programme Background: The ruddy duck Oxyura jamaicensis is a North American bird

introduced to the UK over 50 years ago. A small number escaped from

captivity while others were released. These formed a feral population

which was thought to number around 6,000 by January 2000. By the early

1990s ruddy ducks, almost certainly originating from the UK, began

appearing in Spain where they hybridise with the native white-headed

duck Oxyura leucocephala. In the long-term hybridisation could lead to

the extinction of the white-headed duck unless the threat from the ruddy

duck is removed. Until recently the UK held around 95% of Europe’s ruddy

ducks but following several years of research into control methods, a

five-year eradication programme financed by the EU LIFE-Nature Programme

and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs began in

September 2005. The Spanish Ministry of the Environment is a partner in

the project, and the programme is managed by the Food and Environment

Research Agency (Fera). Background: The ruddy duck Oxyura jamaicensis is a North American bird

introduced to the UK over 50 years ago. A small number escaped from

captivity while others were released. These formed a feral population

which was thought to number around 6,000 by January 2000. By the early

1990s ruddy ducks, almost certainly originating from the UK, began

appearing in Spain where they hybridise with the native white-headed

duck Oxyura leucocephala. In the long-term hybridisation could lead to

the extinction of the white-headed duck unless the threat from the ruddy

duck is removed. Until recently the UK held around 95% of Europe’s ruddy

ducks but following several years of research into control methods, a

five-year eradication programme financed by the EU LIFE-Nature Programme

and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs began in

September 2005. The Spanish Ministry of the Environment is a partner in

the project, and the programme is managed by the Food and Environment

Research Agency (Fera).

Progress in the UK : It was estimated that at the beginning of the eradication programme the UK population was around 4,400 birds, although it is now thought that this was probably an underestimate. To date 6,200 birds have been culled, of which approximately one third were immature birds. The strategy has been to target certain key sites with the aim of achieving rapid reductions in the population. To date all control has been by shooting. Winter shooting has been the critical element in the success of the programme to date, as a large proportion of the total population concentrates on a small number of traditional wintering sites each year. Shooting on sites is by agreement with the site owners, and has been carried out on over 100 sites since September 2005. Although the eradication programme is controversial in some quarters, the support of the major conservation organisations in the UK such as the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) and the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust have been important in helping to persuade owners to allow access. Monitoring of progress: Since the start of the programme, the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT) has carried out independent surveys of key ruddy duck wintering sites in the UK as a way of the monitoring progress. As the eradication has progressed and numbers on the principal wintering sites have fallen, more sites have been surveyed to ensure better coverage and accuracy. A co-ordinated counts of over 100 sites, including all major wintering sites, was carried out by WWT in Great Britain in January 2009 and 687 ruddy ducks were recorded. Since then, Fera has culled another 470 birds. Although there has been a large decline in numbers in recent winters, the population has remained concentrated on relatively few sites. In January 2009 the top 20 sites held 90% of the total number counted. This suggests that ruddy ducks are not becoming more widely dispersed as a result of the eradication programme. Three separate counts in Northern Ireland between October 2007 and March 2008 found a peak count of only 27 ruddy ducks. It is clear that the UK ruddy duck population had declined dramatically since the programme began, but estimating remaining numbers is difficult. However, it seems likely that there are currently in the region of 400 to 500 individuals left in the UK. The eradication programme is due to continue until at least August 2010 and we expect to continue to make good progress in further reducing the population. If full eradication is not achieved by then, we will be in a good position to estimate the time and funding required to eliminate the few remaining birds. Progress in Europe: In other European countries, it appears that France and the Netherlands currently hold viable populations, and numbers in Belgium have increased in recent years. Despite obligations under a number of international treaties, progress in other European countries has been slow and as recently as September 2008 the African and Eurasian Waterbird Agreement (AEWA) strongly urged France and the Netherlands in particular to establish or set up eradication measures to prevent the spread of ruddy ducks in Europe. Ruddy duck numbers in France have been slowly increasing, and in winter 2007/08 the population was estimated to be around 350 birds. The French authorities have been carrying out control for several years but now recognise that the effectiveness of their control programme must be increased if eradication is to be achieved. To date there has been no control of ruddy ducks in the Netherlands, although peak numbers there have declined in two of the last three winters, from 97 in winter 2005/06 to 60 in winter 2008/09. This could suggest possible movement of birds between the Netherlands and the UK. However, the breeding population in the Netherlands has increased in recent years, and was estimated at 22 pairs in 2008. The Dutch Government has recognised the need to eradicate ruddy ducks in the Netherlands and is currently making the necessary administrative changes which should allow this. In Belgium three breeding pairs were present in 2008 and this has increased to 4-5 pairs in spring 2009. Shooting of these birds is difficult due to their location, so attempts are to be made to trap them. In Spain the control programme is ongoing and six ruddy ducks were seen in Spain in 2008, all of which were culled. No hybrids were reported in Spain in 2008.

Conclusions: Good progress has been made in recent years in reducing the

ruddy duck population in the UK and this is set to continue. However, it

is clear that ruddy duck populations in other European countries (most

notably France and the Netherlands) are becoming increasingly important.

Even if full eradication from the UK is achieved, this will prove

worthless unless other populations are reduced and eradicated. More

information can be found at www.nonnativespecies.org/Ruddy_Duck/index.cfm

or contact Iain Henderson, Food and Environment Research Agency, Sand

Hutton, York. YO41 1LZ, UK (email: iain.henderson@fera.gov.uk) |

||||||||||||||||||||

NEW PUBLICATIONS IUCN Report on “Marine menace: alien invasive species in the

marine environment” IUCN Report on “Marine menace: alien invasive species in the

marine environment”This report presents an overview of the marine invasive species issue focusing on causes, pathways, damages and impacts, and the efforts for prevention, detection and early response, awareness and education, and eradication and control. It provides various case studies, including the stories on zebra mussel, the giant red king crab, Atlantic salmon, the snowflake coral, the comb jelly, killer seaweed, Japanese starfish, Mediterranean mussel, smothering by seaweed, small flea, green crab, oysters, Spartina, Cholera, and Tilapia. For downloading of the report, http://www.cbd.int/invasive/doc/marine-menace-iucn-en.pdf

UNESCO Report on “Marine spatial planning: A

step-by-step approach toward ecosystem-based management”

These 10 steps are not simply a linear process that moves sequentially

from step to step. Good practice shows that MSP is a continuous and

iterative process in which many feedback loops should be built into. All

steps of the guide are largely based on the analysis of actual MSP

practice from around the world. A draft text of the guide was refined

through two “fine-tuning” meetings. A first meeting was held in the

Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States of America. A second was

held in Ha Noi and Ha Long Bay, Vietnam. Finally, three review meetings

were held with expert groups of marine scientists and managers. The

UNESCO MSP team is currently working on a web-based application of the

guide that will be updated continuously. The team is also attracting

additional resources to transform the MSP guide into training and

capacity building modules, which would further facilitate effective

application of the ecosystem approach to the conservation and

sustainable use of marine biodiversity. For more information or

downloading of the guide, please visit: ioc3.unesco.org/marinesp. UNESCO Report on Global Open Oceans and Deep Seabed (GOODS)

Biogeographic Classification

Recognizing these realities, UNEP developed a report providing insight and guidance on how ecosystem integrity and water security are inexorably linked. This approach recognizes that (1) continued provision of ecosystem services depends on sustainable and properly-functioning ecosystems; and (2) water security lies at the core of sustainable ecosystems. In discussing these interrelations, the UNEP report notes that actions to ensure ecosystem services and water security must be a priority of governments, and UN and other relevant organizations. Recommended actions in pursuit of this goal include: (1) recognizing and optimizing ecosystem services during – rather than after – development and implementation of national ecosystem and related water resources plans and policies; (2) optimizing ecosystem services as a core goal in activities and programmes implemented by member organizations of UN-Water; (3) developing and implementing activities directed to enhancing ecosystem functioning; (4) engaging partnerships to promote balanced ecosystem services (e.g., UN-Water); (5) promoting optimized and balanced ecosystem services through relevant global venues (e.g., World Water Forum; CSD); and (6) facilitating substantial activities and programmes directed to optimizing and balancing water-related ecosystems services and facilitating their sustainability. In making these recommendations, UNEP also suggests that water security and ecosystem services deserve the same consideration in national development programmes as social welfare and economic growth, since they are basic components of sustainable development. UNEP unveiled its report as a contribution to the 4th World Water Development Report, both launched at the 5th World Water Forum in Istanbul, Turkey, in March, 2009. The UNEP report, “Water Security and Ecosystem Services – the Critical Connection,” further discusses the basic interrelations between water security and ecosystem services, and their importance to both human well-being and ecosystem sustainability. UNEP also developed a companion report highlighting a number of case studies illustrating specific water-related ecosystem management interventions and their results. This latter report, “Water Security and Ecosystem Services – the Critical Connection: Case Studies,” highlights watershed-specific activities directed to sustaining a range of ecosystem services. They range from dam construction aimed at restoring the Aral Sea freshwater environment; to habitat restoration in a binational Latin American river system, to enhancing fisheries in a coastal lake in India, to re-creating environmental flows in the mid-reaches of a tributary system to the Laurentian Great Lakes, to balancing human and ecosystem freshwater needs related to the Panama Canal.

These reports can be obtained from UNEP’s Division of Environmental

Policy Implementation, Nairobi, Kenya, and also are accessible on its

website (www.unep.org/depi/). | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Other useful website links

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Contributors Geoffrey Howard and Sarah Simons (GISP), Diana Mortimer (JNCC, UK), Fanny Douvere and Charles Ehler (UNESCO), Salvatore Arico and Julian Barbière (UNESCO), Walter Rast (Texas State University, USA) |

||||||||||||||||||||

|